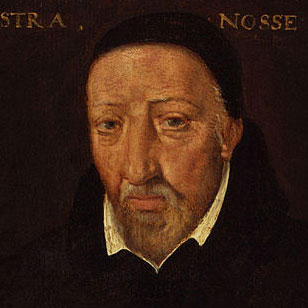

Catherine de Medici owed her position as consort of Henri II to the political manoeuvring of her father-in-law, Francis I of France and his alliances with Popes Leo X and Pope Clement VII, both members of the Florentine de Medici family, to combat Spain and the Holy Roman Empire.

The Medicis were not longstanding French allies. Having lost control of Florence in 1494, they were desperate to restore their former status and fortune, built up by Lorenzo the Magnificent. Despite sorely depleted finances, his younger sons, Giovanni and Giuliano, backed a group of Italian States to defeat the French, in return for help to bring them back to power in Florence. Giovanni, already a Cardinal, was soon elected Pope as Leo X and took Giuliano with him to Rome to extend Medici influence. Their nephew, Lorenzo II, was left to control Florence, with the backing of Papal funds.

In 1515, Giuliano was sent to meet Francis I in Bologna to agree an alliance between the French Crown and the Papacy. Francis provided Giuliano with the French Dukedom of Nemours, and marriage to his aunt, Philiberta of Savoy, but Giuliano died within a year. To maintain this alliance, Leo appointed Lorenzo II, now aged twenty-six, to attend the baptism, on 15 April 1518, of the French King’s first son, the Dauphin Francis for whom Leo became godfather. The King offered to arrange Lorenzo’s marriage to his extremely wealthy kinswoman, the sixteen-year-old Madeleine de la Tour d’Auvergne. Despite Lorenzo’s ‘strutting grandiosity’, Francis hosted a spectacular wedding ceremony at Amboise with dazzling entertainments, and Madeleine was soon pregnant.

The couple returned to Florence for the birth of their daughter Catherine. Yet within a few months, first Madeleine and then Lorenzo died, she of puerperal fever and he, allegedly, of syphilis. The orphaned Catherine was removed to Rome to the care of Pope Leo, who intended that she should marry a Medici cousin, Ippolito, thus becoming the ruling couple of Florence. Yet Leo died on 1 December 1521. By then, he was being assisted by his ambitious cousin, Cardinal Giulio de Medici. Giulio had an illegitimate son, Alessandro, who he had ambitions to promote to Florence in preference to Ippolito and Catherine.

Before Leo’s death, Francis I’s great rival, Charles I of Spain, had been elected Holy Roman Emperor as Charles V, and had pressurised Leo into alliance with him. He was no supporter of the Medicis, and nominated Hadrian VI as the next Pope. Giulio retired to Florence, accompanied by Catherine, Ippolito and Alessandro, who were housed with relations. Although they lacked access to Papal revenues, luck came to their rescue, when, in September 1523, Hadrian died, possibly as a result of poison. Giulio used every bribe at his disposal to gain election as Pope Clement VII.

Despite Clement’s scheming, Charles V remained in ascendancy and, on 6 May 1527, his unpaid Imperial troops ransacked Rome. Clement was forced to raise a ransom of 500,000 ducats by melting down Papal artefacts. With Florence’s resources exhausted by Medici extravagance, the Florentines were lukewarm about supporting the Medicis, particularly when Clement proposed Alessandro as their future ruler. On 17 May 1527, a crowd of Florentines stormed the Medici Palace. Although Ippolito and Alessandro escaped, the eight-year-old Catherine was left to face the mob. Having been held hostage at various semi-derelict convents, she was at last moved to the comfort of Santa-Maria Annunziata delle Murate, where she remained for three years supported by the nuns, many from well-to-do Florentine families. With the French being soundly beaten, Pope Clement came to terms with Charles V at the Treaty of Barcelona on 29 June 1529, under which Charles agreed to support Alessandro’s return to power in Florence, if he married Charles’s illegitimate daughter, Margaret of Austria. On Charles’s instruction, his Imperial troops laid siege to the city. In the hope of using Catherine as a bargaining counter, the beleaguered Florentines forcibly removed her from the Murate Convent. She had shorn her hair and wore a nun’s habit expecting to be being executed and was led on a donkey through the angry crowds. Yet her escort protected her.

When Florence fell, Pope Clement reassumed control and Catherine rejoined Alessandro and Ippolito in Rome. She was now expected to make a political marriage. Despite her elegant manners and spirited intelligence, she was small, physically immature and no beauty. To end her affection for Ippolito, now aged twenty, Clement appointed him a Cardinal and sent to Hungary as Papal legate. On 27 April 1532, Alessandro duly married Margaret of Austria and became Duke of Florence.

Catherine was a good catch. After Henry VIII’s illegitimate son, the Duke of Richmond, James V of Scotland and Francesco Sforza, Duke of Milan, were rejected, Francis I proposed his second son, Henri, Duke of Orléans. It was secretly agreed that Pisa, Parma, Piacenza, Reggio, Modena and Leghorn should be annexed to the French Crown as part of her dowry. The Pope promised to back Francis in taking Genoa and Milan and in annexing Urbino for the young couple. The Papacy also promised Catherine a dowry of 100,000 gold écus, to replace her lost revenues from her Florentine estates, and she still retained her mother’s substantial French inheritance. Francis promised her a further 10,000 livres per annum. This was a substantial fortune, but the Pope had achieved an astonishing match for someone not of Royal blood.

Both Henry and Catherine were aged fourteen in 1533 and the wedding took place in Marseilles. A whole quartier of the town was cleared to make space for the celebrations The Pope accompanied Catherine, furnishing her with the finest gowns, and Francis planned a lavish entertainment. The Pope had struggled to raise the agreed dowry of 100,000 écus, but undertook to provide half the sum before the wedding, with two further amounts afterwards. Catherine’s escort included Ippolito and twelve other cardinals, arriving in a fleet of vessels. Francis arrived two days later.

For her official entry to Marseilles, Catherine, ever the brilliant horsewoman, rode a roan and was dressed in gold and silver silk. After the contract signing on 27 October 1533, Pope Clement performed the marriage on the next day. About midnight, the couple retired, but Francis attended their coucher to ensure consummation. He reported that ‘each had shown valour in the joust’. The principal importance for both Francis and the Pope was for Catherine to become pregnant. If she failed, the marriage could be repudiated.

Within a year, Pope Clement was dead. Alexander Farnese, was elected as Pope Paul III, but had no interest in honouring the outstanding instalments of the dowry, or in backing Francis’s territorial ambitions in Italy. Catherine’s political importance suddenly disappeared, but the Italian shopkeeper’s daughter had married well above her station. When the Dauphin Francis died suddenly on 10 August 1536, the shopkeeper’s daughter from Florence was destined to become Queen of France, but was still not pregnant.

Henry did not find Catherine attractive and soon took Diane de Poitiers, seventeen years his senior as his mistress. Yet Diane became Catherine’s unexpected ally. So long as she failed to conceive and was not repudiated, the politically astute Diane retained Henry’s ear. Catherine resorted to every possible potion suggested by Diane in the hope of becoming pregnant. She drank drafts of mule’s urine as an inoculation against sterility. Poultices were applied to her genitals during love-making. These included ground stag’s antlers and cow dung, the smell of which was relieved by crushed periwinkle blended with mare’s milk. These can hardly have been an aphrodisiac for the reluctant Dauphin. She went to Francis I in floods of tears, admitting that she should be repudiated, but the soft hearted King agreed to give her more time, against the better interests of his dynasty. Diane continued to send an unenthusiastic Henry (who soon became King as Henry II) to her on a regular basis. At last she consulted a new doctor, and whether by good luck or his sensible advice, almost immediately became pregnant. The Dauphin Francis was followed by a string of children, few of whom enjoyed robust health. Even now Catherine still found herself subordinated to Diane de Poitiers, but she bided her time. As her political acumen developed, she shrewdly positioned herself as Queen Dowager acting as guardian of the Crown on her children’s behalf, initially with the support of the Guise family.

On 30 June 1559, Henri II arranged a spectacular jousting tournament in Paris in celebration of his daughter Elisabeth’s marriage to Philip II of Spain. This was to be attended by the bridal couples and their assembled guests. Catherine begged him not to take part after a premonition of his fate, but he was mortally wounded when a lance splintered after striking his visor. Henry died in agony ten days later and the fifteen-year-old Dauphin Francis, now married to Mary Queen of Scots, became King. Although Mary’s Guise uncles took control, Catherine was concerned at their ultra-Catholic and Imperialistic policies, and imperceptibly wean the Royal couple away from them. When the sickly Francis died in the following year, she was positioned to take control of Government on behalf of her next son Charles IX and Mary was packed off back to Scotland.

Catherine was now positioned to control the French Government on behalf of her children, balancing Catholic and Huguenot interests in order to maintain peace. Her death coincided with that of her third son, Henry III in 1589 when the house of Valois was succeeded by the Bourbon Kings of France.

References

Leonie Frieda, Catherine de Medici, Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2003