Note: The numbering of the Earls of Mar causes confusion. There were two titles, the ancient earldom of Mar, which passed through the female line, and a title originally created for Lord James Stewart on his marriage. When Lord James became Earl of Moray, John Erskine received the new Mar Earldom, but it passed only through the male line. To gain restoration of the original title, John claimed descent through five Lords Erskine who were deemed de jure Earls of Mar, although they were never known by that title. Burke’s Peerage 1936 numbers these five de jure Earls, making this Earl of Mar the 22nd in line. Wikipedia does not, so this John becomes the 17th Earl. I prefer to follow Burke’s peerage, which is also followed by Stirnet.com (the principal source of all my genealogical data).

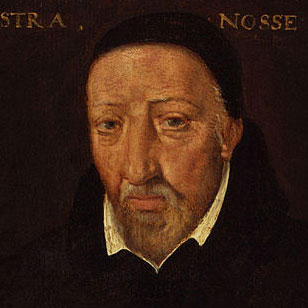

John 6th Lord Erskine was his father’s third son and was brought up for the church being appointed Abbot of Dryburgh and Commendator of Inchmahone in 1547. His eldest brother, Robert was killed at the battle of Pinkie Cleuch in 1547 and Thomas, the second son, died about four years later, allowing him to succeed his father as 6th Lord Erskine in 1552. He was an early convert to become a Reformer, but in 1557, when he married Annabella Murray, daughter of William Murray of Tullibardine, she remained a staunch Catholic.

The Lords Erskine were hereditary governors of Stirling Castle and traditional protectors of the heirs to the throne. On succeeding his father, Erskine also took over the governorship of Edinburgh Castle. During Lord James Stewart’s efforts to oust the Queen Regent’s French troops, he remained neutral and, in 1559, turned the Castle guns on him when he tried to take Edinburgh. As a confirmed Royalist, albeit a Presbyterian, he met Mary Queen of Scots when she arrived in Edinburgh on her return from France and joined the Privy Council as Lord Treasurer, being recognised as a moderate between polarised Catholic and Presbyterian factions. Despite being no intellectual match for Lord James Stewart and the other political leaders, Mary recognised his honesty, and he held both Edinburgh and Stirling Castles with impartiality at a time when integrity was in short supply. His daughter Mary was soon appointed one of the young Queen’s ladies-in-waiting.

The Erskines had always believed that they should rightfully be Earls of Mar. The claim of Sir Robert Erskine had been acknowledged in 1395 by a charter signed by Robert III and he adopted the title in 1438. Four years after his death in 1453, James II arranged an assize of error against the grant, and Sir Robert’s son Thomas was debarred on grounds of illegitimacy. There was no justification for this, but the Earldom held valuable estates, which devolved on an impoverished Crown; the title now passed to successive younger sons of the Scottish Kings. On 7 February 1562, it was announced that the earldom had been granted on marriage to Erskine’s nephew and Mary’s half-brother, Lord James Stewart. He had no wish to fall out with his uncle, and it was never intended that he should hold the title in the longer term. He sought the earldom of Moray, the estates of which were now controlled by the Earl of Huntly, who was opposing his Government. He needed to establish a powerbase in the Catholic north to assert authority and to complement his traditional support from the Reformers in the Burghs (and more clandestinely from the English). His objective was to delay announcing his Moray grant to a time, which would cause the maximum provocation to Huntly. As soon it was announced, the grant of the Mar title was withdrawn from him.

Three years later, when Mary was contemplating marriage to Lord Darnley, she found herself facing vehement opposition from the newly created Moray. She needed Erskine’s support. His wife, Annabella, who was now a close confidante of the Queen, persuaded him that it was a true love match, and Mary at last confirmed his family’s long held ambition by issuing a Royal Charter making him Earl of Mar [1]

Following Mary’s marriage to the Catholic Darnley, Moray lost hope of retaining authority in Government, and he took up arms against Mary. Yet he had insufficient support. After skirting round her army, he arrived at Edinburgh, where Mar, at the Castle, threatened his men with the Castle guns and forced him to retire. Mar remained closely allied to Mary, being nominated as one of three members of the Regency if she should die during the birth of Prince James. Afterwards, Mary went to recuperate with the Mars at their home at Alloa Tower near Stirling. In accordance with tradition, the Mars took charge of the Prince for his upbringing. Initially they were at Edinburgh Castle, but, in August 1565, Mary moved them to Stirling, which she considered more secure.

After Darnley’s murder, the Mars were taken in by the propaganda on Edinburgh placards, which portrayed the murder as a crime of passion between the Earl of Bothwell and Mary. Annabella’s brothers, William Murray of Tullibardine and James Murray of Pardewis, seems to have been behind the rumours. This rapidly cooled their fond relationship with Mary. When Mary visited Stirling intending to escort the Prince back to Edinburgh, Mar acted treasonably by refusing to allow him out of his control. Mar was soon at the forefront of those nobles opposing Mary’s remarriage to Bothwell. After it had taken place, Mary went to Stirling for a second time seeking to move the Prince under Bothwell’s control. George Buchanan, who shared Mar’s concern, reported that Bothwell ‘did not consider it to his own security to protect a boy who might one day become the avenger of his father’s death; and he wanted no other to stand in the way of his own children in line of succession to the throne’. Mar thwarted Mary by retaining the Prince under his control and, without Bothwell being with her, she had no means of enforcing her will. After spending most of 22 April 1567 at Stirling, she left without James on the following morning, but pressed Mar ‘to be vigilant and wary that he was not robbed of her son’. When the nobles met at Stirling four days later, he would not let the Prince out of his sight.

This meeting was followed by a much larger gathering at Stirling on 6 May with a common goal to bring Bothwell down. With Moray keeping his hands clean in France, the Earl of Morton co-ordinated the representatives of all factions, and was given the task to ‘manage all’. They signed a bond to ‘pursue the Queen’s liberty, preserve the Prince from his enemies in Mar’s keeping, and purge the realm of the detestable murder of our king’. The choice of Stirling, where Mar was Governor, demonstrates that he now fully supported them. When the nobles left to muster troops with which to challenge Bothwell, Mar remained at Stirling to protect Prince James. He was now exposed to any attempt by Bothwell to gain control. Although Randolph reported that he planned to send the Prince to France to prevent the nobles from ruling in his name, his objective was to resist Bothwell, and he prepared for a siege.

On 8 June, having mustered their forces, the nobles again met at Stirling and had Mar’s approval to challenge Mary and Bothwell. Mary had sent the Bishop of Ross to reiterate that under no circumstances should he deliver James to anyone but herself. Recognising the strategic importance of controlling the Prince, Bothwell may have wanted him sent to France. He repeatedly asked for him to be delivered to Mary and himself. Sir James Melville reported, ‘but my Lord of Mar was a trew nobleman, and would not delyuer him out of his custody, alleging that he could not without consent of [Parliament]’.With Mar providing a family environment that James needed, Mary’s son was in safe hands.

Throckmorton recognised Mar’s key role in controlling James, realising that his future was dependent on who Mar chose to support. Although he asked Mar to provide Mary with protection, Mar replied: ‘To save her life by endangering her son or his estate, or by betraying my marrows, I will never do it, my Lord Ambassador, for all the gowd in the world.’ In Mar’s eyes, Mary was morally indefensible and, with his absolute control of the Prince, his ‘incorruptible integrity’ sealed Mary and Bothwell’s fate. After supporting the cause to defeat them, he signed the agreement to commit Mary to Lochleven and supported her abdication in favour of a Regency headed by Moray, his nephew.

On 29 July, at the age of thirteen months, James was crowned King James VI in the Protestant church at the gates of Stirling Castle, being carried by Mar throughout the ceremony. After Mary’s escape from Lochleven, James remained securely under his control, and when she was back in captivity in England, she wrote plaintively to Mar to guard him well and not to let him out of his control without her express permission. With Mary being held in England indefinitely, Elizabeth sought to have James brought to England to be brought up by his grandmother, Lady Margaret Lennox, a plan with which Mary agreed, but in 1570, with the Earl of Lennox becoming the Scottish Regent following Moray’s assassination, he showed every respect for the Mars’ devoted care of his grandson, and James stayed where he was. To ensure that he was brought up as a Reformer, Lennox (despite his Catholicism) gave Buchanan charge of the Prince’s education, bringing him up to believe in his mother’s guilt.

When Lennox was assassinated at Stirling in 1571, Mar, as a neutral, ‘enjoyed such a general respect’ in the desire for peace that he gained universal support to replace him as Regent. He did not prove an astute leader.

Though actuated always in the discharge of his public duties by a high sense of honour, he had neither the force of character nor the power of initiative to enable him to carry out an independent policy in difficult circumstances.

With Elizabeth’s encouragement, the Earl of Morton rapidly took practical control, leaving Mar out-manoeuvred. He arranged for Angus, his ward, to reside with Mar to gain experience and, no doubt, to keep his uncle informed of what was going on. This led to Angus’s marriage to Mar’s daughter Mary on 16 June 1571, although she died two years later. Although Mar continued efforts to stamp out lingering support for Mary, he did not act with great vigour. By now Elizabeth was looking for an excuse to return Mary to Scotland, but held with security of her life. On 9 October, Killigrew, the English ambassador, came to Edinburgh to discuss this secretly with Mar and Morton. Morton immediately saw through Elizabeth’s motive and said that the Regency could only agree, if Mary faced a public execution with 2,000 English troops present to confirm her approval. Killigrew could not of course accept this. Although Mar saw her execution ‘as the only salve for the whole Commonwealth’, he was struck with horror at the reality of it and became speechless. Sir James Melville recorded: ‘He departit to Stirling, where for grief of mynd he deit [died]’. He became violently ill, passing away on 28 October 1572.

After Mar’s death, Annabella continued to devote herself to the young King, now supported by Mar’s brother, Sir Alexander Erskine of Gogar.

[1] Mary’s lawyers confused the grant by reinstating the original title, which passed through the female line, and then by passing on to him the new one originally offered to Moray, which did not. In 1875 the House of Lords upheld the view that the entail of the original title had been replaced by the new one, allowing the Earls of Mar and Kellie, represented by the male Erskine line, to hold both grants. However this decision was amended in 1885 when the female line was granted the original title becoming Earls of Mar, but leaving the newer one with the Earls of Mar and Kellie.