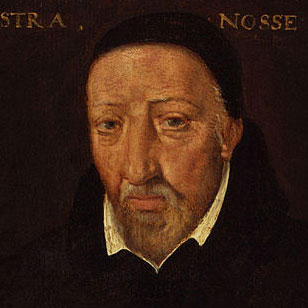

Lord Robert Dudley was one of thirteen children of John Dudley, Earl of Warwick, later Duke of Northumberland. In 1550, at the age of eighteen, he married Amy Robsart, although they had no children. In 1553, his father, now acting as Protector for the consumptive Edward VI, attempted to avoid Mary Tudor, as a Catholic, from succeeding to the English Crown, and he promoted Lady Jane Grey to succeed Edward on the English throne. Lady Jane was the grand-daughter of Henry VIII’s younger sister, Princess Mary, and had the merit of being Protestant. She was quickly married off to Lord Robert’s brother, Lord Guildford Dudley.

Lady Jane’s accession to the English throne resulted in both Henry VIII’s daughters, Mary and Elizabeth, being overlooked. Mary took up arms and marched on London and, supported by Elizabeth, was swept to power as England’s Catholic Queen. Northumberland was executed for high treason, while Lady Jane Grey and Lord Guildford Dudley were imprisoned in the Tower. Efforts were made to restore a Protestant monarchy and Sir Thomas Wyatt led a rebellion designed to place Elizabeth on the throne. Although this failed, there was no evidence that she was implicated in the plot, and none of those around her, including Lord Robert Dudley, revealed any part she may have played in it. Yet the rebellion resulted in Lady Jane Grey and Lord Guildford Dudley being executed, although they were not involved. Lord Robert was also condemned, but was freed in the following year to join Philip II’s forces in their successful campaign at St-Quentin. Elizabeth was lucky to survive but there was no evidence against her.

In 1558, when Mary died and Elizabeth became Queen, Lord Robert was appointed her Master of the Horse, and became her close favourite. Despite his marriage to Amy Robsart, Elizabeth established strong attachment to him, much to the chagrin of Elizabeth’s Secretary of State, William Cecil, who strongly disliked Dudley. In 1560, Amy Robsart, who rarely came to Court, and seems to have suffered from a long term illness, fell down the stairs while staying at Cumnor Place in Oxfordshire and was killed in the fall. Although the Coroner’s jury recorded the death as ‘misfortune’, Cecil immediately planted rumours that Amy had been pushed, casting a slur on Lord Robert. Although Elizabeth had undoubtedly contemplated marriage to him, she now realised that she could not risk being implicated in the scandal that would result, and Cecil warned her that he would resign if she did so.

Dudley remained as a leading statesman. In 1564, Elizabeth nominated him to marry Mary Queen of Scots in an effort to provide a husband for this Catholic Queen, who would assure her loyalty to England. She even created him Earl of Leicester to improve his status. Yet she started to have cold feet about losing Lord Robert for herself, and quite impracticably proposed that after their marriage they should live in a ménage à trois in London, leaving the Earl of Moray to govern in Scotland. Cecil had no enthusiasm for allowing Leicester to marry the heir to the English throne, and he managed to scupper the proposal by refusing to Mary’s pre-condition that she should be confirmed Mary as Elizabeth’s heir. Leicester was also reluctant, as he still hoped that he might marry Elizabeth. Between Leicester and Cecil, they managed to arrange for the politically inept and objectionable Henry Lord Darnley to be sent to Scotland as Mary’s suitor. To everyone’s surprise, she immediately fell for his good looks and married him, despite belated attempts to restore Leicester in his place.

Leicester remained for some time at the centre of English politics as a result of his close association with Elizabeth, but he was not trusted by his colleagues. He cast himself in the role of Kingmaker to support the Duke of Norfolk in his secret plan to marry Mary, who was by now being held under house arrest in England, following the murder of Darnley. Leicester later had to grovel to Elizabeth for his part in promoting the marriage, particularly as he also attempted to persuade her to dismiss Cecil. By 1573, he realised that his hopes of marrying Elizabeth had evaporated and he secretly married Douglas Howard, the daughter of Lord Howard of Effingham. It is not at all clear that Elizabeth was aware of this marriage, but they had a son, Sir Robert, in about 1574. Leicester later repudiated the marriage, causing his son to be deemed illegitimate (although he later claimed to be Earl of Leicester and Duke of Northumberland). In 1577, Leicester met Mary, by chance, while taking the waters at Buxton, where he had been sent by Elizabeth to lose weight.

In 1578 Leicester married Lettice Knollys, Elizabeth’s cousin and widow of the 1st Earl of Essex. In the following year their son, Robert, Lord Denbigh, was born, but his death in 1584 caused great distress. In 1585 Leicester was sent on a military expedition, which he largely funded, to support the Dutch rebels against Philip II in the Low Countries. He did not prove a successful commander, and on arrival one hundred and forty of his men were killed as they disembarked. Leicester was by now in poor health. He returned to England, but died aged fifty-five on 4 September 1588 shortly after the defeat of the Armada, causing great sadness for Elizabeth at the moment of her greatest triumph.