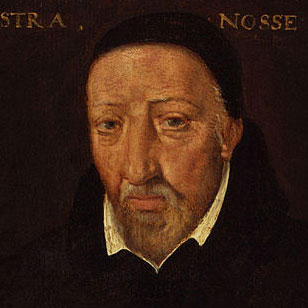

As a young man George Talbot saw military service under Protector Somerset in the ‘Rough Wooings’ in Scotland and he married Gertrude Manners, daughter of the 1st Earl of Rutland, by whom he had six children, although she died in 1566. In March 1568, he married Bess of Hardwick, the wealthy widow of Sir William Cavendish of Chatsworth, who was a year older than himself. To cement their love, it was agreed that his eldest surviving son, Gilbert, aged fifteen, should marry her daughter Mary Cavendish aged twelve, and Henry Cavendish aged seventeen married Grace Talbot aged eight. The joint weddings of their children took place on 9 February 1568 followed by that of Shrewsbury and Bess a few weeks later.

Shrewsbury was already one of the richest landowners in England with vast estates, which he worked to full advantage, mining coal, iron and lead, while also owning and operating the spa at Buxton, where he had built a four-storey house with thirty rooms, and a ‘great chamber’ around the spring. In addition to Buxton and his principal property, Sheffield Castle with its Park, he owned Sheffield Manor (within the Park), Wingfield Manor, Worksop Manor, Welbeck and Rufford Abbeys, together with several houses in London. He also held leases from the Crown, particularly over Tutbury Castle and Abbey in Staffordshire. When the Duke of Norfolk fell under a cloud, Shrewsbury became Earl Marshal of England, a role traditionally reserved for the senior peer of the realm

Together, Shrewsbury and Bess offered one of the few households able to bear the enormous financial burden of maintaining Mary Queen of Scots under house arrest, but living at Elizabeth’s request as a Queen with her own entourage. Elizabeth did not want to have to foot this bill herself. Although Mary could afford, initially at least, to pay her staff from her French income, this became increasingly irregular, and the Scottish Regency blocked any transfer from her Scottish revenues. Despite his huge fortune, even Shrewsbury was caused embarrassment by the financial pressure that Mary posed.

Although Mary was held initially at Bolton Castle in Yorkshire, the home of Lord Scrope, William Cecil wanted her nearer to the English heartland and away from centres of Catholic intrigue in the north. Shrewsbury was a Protestant and had attended the concluding part of the Conferences at which evidence had been submitted implicating her in the murder of her husband, Lord Darnley. Elizabeth approached him at Court to give him the position ‘in consequence of his approved loyalty and faithfulness, and the ancient state of blood from which he is descended’, and he was also appointed a Privy Councillor. She gave strict instructions that he was not to allow Mary to work her charms on him. Mary was to remain with them almost continuously for fifteen years until 1584. He understood the risk of her becoming the focus for Catholic intrigue in England and proved an ideally attentive and fussy jailer. Despite periodically denouncing her as a ‘foreigner or papist or my enemy’ to protect his credentials, he was at heart a Conservative, making him suspicious of Cecil, and he came to have much sympathy for his prisoner.

Shrewsbury was advised from London that he should hold Mary at Tutbury Castle, although Bess saw that its dilapidated state made it as the least satisfactory of their homes. Tutbury was originally built by John of Gaunt, and it was leased to Shrewsbury by the Duchy of Lancaster. It was large enough to be a fortified town, but much was falling down, and the remainder was at best indifferently repaired. Mary found it the most inhospitable of the places where she was held. Not only was it damp, cold and drafty, but bounded by a foul smelling midden forming a marsh on one side. On 25 January 1569, Mary set out with her entourage from Bolton through desperate winter weather, arriving at Tutbury nine days later. She was greeted by Shrewsbury and Bess, who made every effort to make her comfortable, even allowing a man, going under the name of Sir John Morton, to be introduced, although he was secretly a Catholic priest. Mary continued to make a play of studying the Protestant faith, and undertook needlework of very fine quality with Bess.

Despite poor health from the continuing pain in her side, and her uncomfortable surroundings, Mary continued to maintain a considerable household. Having insisted that she should live as a Queen, Elizabeth made it difficult for the Shrewsburys to achieve economies. Mary was not about to lower the standards that she had come to expect in France, and had introduced into Scotland. Shrewsbury was initially instructed by Elizabeth to reduce Mary’s household from sixty to thirty, in addition to her women and grooms. He was a soft touch and had difficulty in persuading her to make economies, and her staff crept up again to forty-one. He complained to Cecil that ‘the Queen of Scots coming to my charge will soon make me grey-haired’. He soon began a plaintive correspondence with both Cecil and Elizabeth over the cost of her maintenance, and the need for his constant attendance on her. Elizabeth ignored his worries, and complained that Mary seemed to be granted too much freedom. Far from reducing her household, Mary progressively increased it to eighty, requiring Shrewsbury to employ more guards to police comings and goings. He was out of pocket by nearly £10,000 per year. Francis Walsingham, Elizabeth’s Secretary of State, was sympathetic, as he personally was never adequately compensated for his spy network set up largely at his own expense. He hoped that ‘the abatement of the charges towards the nobleman that hath custody of the bosom serpent hath not lessened his care in keeping her’, but Shrewsbury remained stalwartly attentive in his role.

Within two months of her arrival at Tutbury, Shrewsbury was negotiating with Cecil to transfer her to one of his more amenable properties, not least because of the inadequacy of the drains, which could not cope with such a large household. The smell was so intolerable that the only course was to move to a different location, while the unpleasant process of digging them out completely and transporting the effluent could be undertaken without the Royal party being in residence. Another problem was the shortage of local wood, coal, corn, hay and fresh food, so that carts had to be sent from further afield. The damp conditions had done nothing to improve the health of either Mary or Shrewsbury, and his doctor was in constant attendance on both of them. Shrewsbury suffered from ‘gout’, although at this time the term could be applied to arthritis, rheumatism and even kidney complaints. They moved first to Wingfield Manor, arriving from Tutbury on 20 April after a ten day journey. This handsome manor house, ten miles from Chesterfield, was a huge improvement, and even Mary considered it ‘a palace’. By the time of his arrival, Shrewsbury had contracted a severe chill and, for a few hours, there were fears for his life. Sir Ralph Sadler was sent to take charge if the worst were to happen, but Shrewsbury rallied and Mary slowly recovered. After two months, Shrewsbury arranged for her to go to Chatsworth, while Wingfield was ‘sweetened’.

In July, Shrewsbury left Wingfield to take a curative bath for his gout at Buxton, leaving Mary in Bess’s care. This brought him a severe reprimand from Elizabeth, who wanted her under his constant personal supervision. Prominent figures from Court, including both Cecil and the Earl of Leicester visited Buxton, and Shrewsbury made a point of visiting them or sending produce from his estates, in an effort to keep in touch. Eventually even Mary was permitted to make visits to improve her health, but was not permitted to speak to other residents. By November, Shrewsbury had approval to move Mary to Sheffield Castle, his principal home, where she remained for more than two years. Only a mile from the Castle, in its Park, stood another magnificent house, Sheffield Manor, on the site of a former hunting lodge. During Mary’s stay, Shrewsbury extended and rebuilt it, so that she could move there starting in April 1573. Over the next eleven years, she moved between the two Sheffield properties with occasional trips to Chatsworth, surrounded by its wild moorland. This provided fresh air for her health, with riding, coursing her greyhound, hawking and occasionally matches of archery with Shrewsbury.

The Shrewsburys showed off their charge to some of the great local families such as the Manners, Shrewsbury’s first wife’s family, and the Pagets, who had Catholic sympathies. This resulted in a number of musical soirées to relieve Mary’s tedium. There were soon complaints from London that she was enjoying too much social life. In April 1574, Shrewsbury was accused of showing her excessive favour, and even of backing her claim to the English throne. He wrote to Cecil:

I doubt not, of God’s mighty goodness, of her Majesty’s long and happy reign to be many years after I am gone . . . how can it be imagined I should be disposed to favour this Queen for her claim to succeed the Queen’s Majesty. I know her to be a stranger, a papist and my enemy.

He was at pains to explain his care for her security and was forced to curtail her social diversions. Yet, on 24 December 1575, he was rebuke by Elizabeth ‘with plain charging of my favouring the Queen of Scots’. He replied that he had no reason to mistrust her, but, if she posed a threat to Elizabeth, he would deal with her severely.

During the course of the Northern Rising, an attempt was made to free Mary and to back her marriage to the Duke of Norfolk. Her apartments at Wingfield were searched by men armed with pistols and she was returned to Tutbury. Leicester’s brother-in-law, The Earl of Huntingdon, was sent to ‘assist’ Shrewsbury in reducing her staff to thirty. Although Mary complained to Elizabeth, several of Shrewsbury’s servants thought to be sympathetic to her were dismissed and he was castigated for treating her with ‘too much affection’ and having failed Elizabeth ‘in my hour of need’. Mary was moved under Huntingdon’s care to Coventry, where she had to be housed in the Inn as the castle was uninhabitable. She hated Huntingdon, who was a Plantagenet claimant to the English throne, and he started to negotiate with her over her own claim. He seems to have overplayed his hand and, after two months at Coventry, Mary was back under Shrewsbury’s less controversial care at Tutbury.

Shrewsbury was temporarily relieved of his responsibilities for Mary so that, as Earl Marshal, he could chair Norfolk’s trial, and Sir Ralph Sadler was sent to assist Bess. Norfolk was found guilty, and Shrewsbury, who had sympathy for the Conservative cause, wept as he read out the verdict, although Elizabeth dithered about signing the death warrant. Shrewsbury returned to Sheffield with instructions to reduce Mary’s household to ten people and to limit her freedom of movement. She had wept bitterly on hearing of Norfolk’s sentence and wrote vitriolic letters to Elizabeth, praying and fasting on alternate days for his deliverance. This exacerbated her poor health, but despite offering her greater freedom, Shrewsbury left nothing to chance. He had a

good number of men, continually armed, watching her day and night . . . so that, unless she could transform herself to a flea or a mouse, it was impossible that she should escape.

Following Norfolk’s execution, there were rumours that Philip II planned a full scale invasion to overthrow Elizabeth and to place Mary on the throne. This was a dangerous time for the English Government, and Shrewsbury became much more careful in controlling Mary’s movements. On 10 October 1572, he wrote:

This lady complains of sickness by reason of her restraint of liberty in walking abroad, that I am forced to walk with her near unto my castle, which partly stays her from troubling the Queen’s Majesty with her frivolous letters.

To make matters worse, Elizabeth became dangerously ill and there was a fear that Mary might suddenly inherit the throne. As her gaoler, Shrewsbury was extremely perturbed and, on 22 October, wrote to Elizabeth most anxiously. She replied:

My faithful Shrewsbury, let not grief touch your heart for fear of my disease; there is no beholder would believe that ever I had been touched with such a malady,

Your faithful loving sovereign, Elizabeth R.

He found the letter as ‘far above the order used to a subject’, and kept it ‘for a perpetual memory’.

Shrewsbury was showing signs of age and was beginning to suffer from a mental deterioration that manifested itself as a persecution complex. He had become progressively more agitated at not being adequately recompensed for Mary’s maintenance. Yet, in 1577, he seems to have had sufficient resources to start work on building a new ‘great house’ at Worksop to complete the shell begun by his father. This was designed by Robert Smythson, Bess’s architect. He started to blame Bess for undermining his authority by countering his instructions on his building projects. He could see no good in her, likening her to ‘a shrew [1] with a wicked tongue’. By 1580, their marriage was falling apart after some indisputably happy years, and Bess separated from him to live at Chatsworth.

It was quickly rumoured that Bess’s disaffection with her husband was caused by her belief that he was conducting an affair with Mary, who was more than twenty years her junior. In August 1580, Shrewsbury asked if he had offended Elizabeth, seeing her refusal to pay his allowance for Mary as some kind of punishment. This gained a sharp rebuke from her to remind him of his duty. Leicester quickly warned him that there was gossip of his over romantic liaisons with Mary. It was even suggested that Mary was pregnant by him. Mary was totally incensed at this outrage to her honour, and demanded that she should be permitted to come to Court to clear herself. She believed that Bess was behind the rumours, but Bess was almost certainly innocent and subsequently confirmed under oath that there was no impropriety between them, to scotch what may well have been Government inspired propaganda. Yet this did nothing to improve his relationship with her, and he came to refer to her as ‘my wicked and malicious wife’ and ‘my professed’ enemy. He also sought to come to Court, in part to give assurance that there had been no affair between Mary and himself, and in part to try once more to seek recompense for the cost of her maintenance. In the autumn of 1582, he at last arranged to visit London, only to find that permission was cancelled at the last moment. Elizabeth preferred to believe that he was being too lenient with Mary, claiming unfairly that Mary was holding her own Court and riding about at will. She wanted to avoid seeing him, despite his letters professing his loyalty, giving assurances that he saw Mary as ‘a stranger, a Papist, and my Enemy’. Yet he dared not forget that she was dynastically next in line to the throne, and he could be at risk if he treated her as Elizabeth might have wanted.

To allay suspicions of an affair with Mary, Shrewsbury needed to be seen to be reconciled with Bess. He wrote to Leicester, who was at Buxton, asking him to intercede with her at Chatsworth on his behalf, and, with Elizabeth’s approval, Leicester did so. He found Bess greatly distressed that Shrewsbury had become offended against her without reason. Both Elizabeth and her close advisers had much sympathy for her, recognising that Shrewsbury was suffering from mental stress, but they did not immediately remove Mary from his supervision and did nothing to abate the growing cost of her maintainance. Although he agreed to make a new start with Bess, he failed to do so. It soon became clear that he had taken Eleanor Britton, his housekeeper, as his mistress and the marriage had irretrievably broken down. Mary needed a new jailer.

Shrewsbury was not involved in supervising Mary in her latter years or in the discovery of the Babington plot, as a result of which she was tried for treason at Fotheringhay. He tried to avoid attendance on the grounds of ill health, but Burghley warned him that Elizabeth would be concerned that ‘there might be of the malicious some sinister interpretation’. He was required to deliver the sentence for her execution. On 4 February 1587, Robert Beale, Clerk to the Privy Council, met Shrewsbury and Anthony Grey, 9th Earl of Kent, to brief them. After dinner on 7 February, Shrewsbury and Kent came to her rooms to advise that she would be executed at eight o’clock on the following morning. She was already in bed, and had to dress before Shrewsbury could give her the message, but replied: ‘I thank you for such welcome news. You will do me great good in withdrawing me from this world out of which I am very glad to go.’ They also attended her execution, encouraging her to listen to the Dean of Peterborough, who called for her to recant; they offered to pray with her, but she courteously declined. When the axe severed her head Shrewsbury was too overcome to speak. He never really recovered from this ordeal and died on 18 November 1590. Bess lived on, freed at last from her mentally ill husband, continuing improvements to her many properties until her death in 1608 when she was eighty-one.

[1] The Bishop of Coventry and Lichfield, one of the many who approached Shrewsbury seeking his reconciliation to his wife, wrote:

Some will say in your lordship’s behalf that the Countess is a sharp and bitter shrew. . . . indeed, My Lord, I have heard some say so, but if shrewdness or sharpness may be a just cause for separation between a man and wife, I think very few men in England would keep their wives long . . . it is a common jest that there is but one shrew in all the world and every man hath her . . .

Source

The principal source for this summary is:

Mary S. Lovell, Bess of Hardwick, First Lady of Chatsworth, 1527 – 1606; Little, Brown, 2005