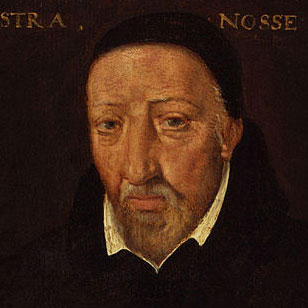

Sir Francis Walsingham was born into a well-connected family in 1532. When his father died two years later, his mother Joyce Denny, remarried Sir John Carey, brother-in-law of Mary Boleyn, who was Elizabeth I’s aunt. He studied at King’s College, Cambridge. After travelling in Europe, he decided to become a lawyer and, in 1552, enrolled at Gray’s Inn. When Mary I came to the throne in 1553, he escaped abroad and continued his law studies at the Universities of Basel and Padua. On Elizabeth’s accession in 1558, he returned to England and, thanks to the patronage of Francis Russell, 2nd Earl of Bedford, became a Member of Parliament. He was a close ally of the diplomat, Sir Nicholas Throckmorton, who had been ambassador in Paris and solicited support for the French Huguenots. He also worked with William Cecil to counteract plots against Elizabeth. Most of these involved attempts to place Mary Queen of Scots on the English throne. At this time, the Duke of Norfolk was secretly contemplating marriage to Mary, and was soliciting backing from Continental Catholic Powers.

Much of the plotting was taking place in Paris, so Cecil seconded Walsingham as Ambassador to France to see if he could root out any treasonable plans before they were fully developed. Walsingham was so ruthless in his efforts to protect Elizabeth that she came to fear and distrust his methods. Unlike Cecil, who only wanted to prevent Mary gaining the English throne, Walsingham wanted evidence, which would result in her execution. Cecil had never gone this far, fearing Elizabeth’s wrath, and not wanting Mary to become a martyr for the Catholic cause. Walsingham was never so concerned to retain Elizabeth’s goodwill, and he was single-mindedly focused on implicating Mary in a treasonable plot.

Walsingham’s initial concern surrounded Roberto Ridolfi, a Papal agent, whose brother operated a bank in Rome. Ridolfi was a ‘bosom creeping Italian’, based in London, also employed by Cecil for his own business, but, like all foreigners, was closely watched. He appeared to be raising money to support a plot against Elizabeth and he provided a messenger service to communicate with Mary, who was under house arrest. Walsingham went to great lengths to infiltrate Mary’s communication network, placing his own men in her employment to decode her ciphered messages. He arranged for Ridolfi to be arrested, but, instead of putting him in the Tower, invited him to stay with him at his home, from where he was released after six weeks. During this time, Ridolfi was persuaded to become a double agent, passing copies of all letters in his delivery system to Walsingham. Walsingham wanted to hear of any plots being put together, and whether Mary and Norfolk were involved. On 25 March 1571, Ridolfi was permitted to leave England, conveniently before he could be brought to trial. From his base on the Continent, he continued to act as the conduit for all correspondence between Mary, Norfolk and their Catholic allies, while still acting as a double agent for Walsingham. He eventually retired to Florence, and lived on there until 1612.

The Bishop of Ross was now using Ridolfi’s communication system to implement a plan, initiated by Mary and Norfolk, to seek military aid from Philip II. Philip’s new ambassador in London, the pompous and inept Don Guerau de Spes was calling for a trade embargo against England. He was now approached by Ridolfi, who had been encouraged by Walsingham to infiltrate his way into the conspiracy, by offering to arbitrate between the Duke of Alva, Philip II’s agent in the Netherlands, and Elizabeth to find a means of stopping the embargo. With Walsingham’s complete knowledge, Ridolfi also advised de Spes that Norfolk and his allies, Arundel and Lord Lumley, wanted to overthrow the ‘low-born’ Cecil, so that they could take their rightful places in Government. They would then realign English foreign policy closer to Spain and Rome. Ridolfi later told the French ambassador that he had a commission from the Pope to help to restore the Catholic faith in England, implying that Mary, with Norfolk at her side, would be placed on the English throne. With these objectives agreed, de Spes provided Ridolfi with £3,000 to give to the Bishop of Ross, and Mary was aware that these funds had been received. So was Walsingham.

As Ridolfi provided the only means of communication between Mary, Norfolk, the English Catholics and de Spes, he also provided the ciphers to encode the correspondence. Walsingham now received all their messages and the code to decipher them. During the remainder of 1571, Walsingham and Cecil monitored each letter waiting to see what evidence came forward. To put him off his guard, Cecil released Norfolk on parole from house arrest. Ridolfi went to discuss the invasion plan with Alva, but Alva quickly mistrusted him and failed to reveal the Spanish plan. This left Walsingham’s infiltration system temporarily in the dark. Yet rumours of an invasion were everywhere. Cecil was seriously rattled and issued a warrant for Norfolk’s arrest, charging him with treason. He also wrote a letter to warn the Earl of Shrewsbury of a project for Mary’s escape to Spain. He claimed that Elizabeth was now ‘certainly assured and much more that Mary labours and devices to stir up a new rebellion in this realm and to have the King of Spain to assist it’. In fact he had no evidence to implicate Mary, who was being extremely careful what she put down on paper.

With rumours of Alva’s planned invasion everywhere, Cecil placed all the channel ports on full alert. This resulted in the arrest of Charles Baillie, a twenty-nine year old Fleming, on arrival at Dover. He was found to be carrying letters in cipher addressed to both the Bishop of Ross and Norfolk with numbers substituted for names. After placing him in Marshalsea prison in London, Walsingham sent his agent, William Herle, to befriend him with an offer to deliver his missives to the Bishop on his behalf. The letters turned out to be relatively innocent communications from exiled participants of the Northern Rising. They had nothing to do with an invasion plan, and Baillie was eventually freed after facing torture. To explain the innocuous letters, Cecil and Walsingham put about a story that the Bishop of Ross had warned Baillie to destroy anything incriminating, but, in reality, he had no opportunity to do so. They then reported that Baillie had told them of a proposed Spanish invasion. Although no plans for an invasion existed, it became referred to as the ‘Ridolfi Plot’ but there was no plot and Ridolfi was not doing any scheming. Cecil and Walsingham could not admit that he was acting as their double agent. Their detailed infiltration of the message system had failed to find any evidence to incriminate Mary.

Following the death of the eighty-seven-year-old Marquess of Winchester, who had been Lord Treasurer since 1550, Cecil succeeded him, taking the title of Lord Burghley in February 1572. Walsingham’s success in turning Ridolfi into a double agent also gained its reward. In December 1572, he was brought back from Paris to become one of the two Secretaries of State, to replace Burghley. In no sense did Walsingham’s appointment sideline Burghley, and he never had the same warm relationship with Elizabeth enjoyed by his predecessor. While Burghley had been her ‘Spirit’, the more shadowy, dark-featured and underhand Walsingham was her ‘Moor’. Burghley remained as head of Government, while Walsingham’s mission was to eliminate Catholic sympathies in England and to provide evidence to implicate Mary in a treasonable plot, so that she could be executed. He set up a powerful network of spies to infiltrate the Catholic hierarchy and to seek out culprits. Many Jesuits fell into his merciless hands. He handed them over for torture to his agent Sir Richard Topcliffe at the Tower, portraying them as traitors aiming to transfer England into the hands of Spain.

When the Earl of Shrewsbury’s marriage to Bess of Hardwick became irretrievably broken down, Mary needed a new jailer. Walsingham chose Sir Amyas Paulet, who he had known in Paris and had been ambassador there after him. Walsingham knew he was immune to Mary’s charms, as he had witnessed much of the intrigue on her behalf while in France. Paulet treated her as a criminal, tightening the regime round her to prevent her receiving or sending secret correspondence. He confirmed to Walsingham: ‘I cannot imagine how it may be possible for them to convey a piece of paper as big as my finger.’ He even refused permission for her to exercise on the walls, fearing she could signal to sympathisers. She was permitted to write only to the French ambassador in London, and he read her letters before they were sent.

Walsingham also took an interest in affairs in Scotland. In May 1582, the Spanish ambassador in Scotland sent a message concerning a new Spanish invasion carried but the courier was intercepted at the Border. This alerted Walsingham, who began monitoring correspondence between the French ambassador in London and his Scottish agent. As the French were not involved, this proved a red herring, and he learned nothing to incriminate Mary. When the devious Esmé Stuart, Duke of Lennox was exiled from Scotland at the instigation of a group of Protestant Lords, he arranged for him to be interviewed, but failed to establish his religious persuasion. When the tables were turned against the Protestant Lords led by the Earl of Mar and they too were forced into exile, he persuaded Elizabeth to provide them with financial support. With James no longer under their control, in August 1583, Walsingham came to Scotland in a forlorn attempt to regain English influence. He was furious when James refused to listen to his advice, telling him:

Young princes were many times carried into great errors upon an opinion of the absoluteness of their royal authority and do not consider, that when they transgress the bounds and the limits of the law, they leave to be kings and become tyrants.

As the ultimate spymaster, Walsingham continued his infiltration of Mary’s communication network, seeking early warning of any Catholic intrigue. His network had become so comprehensive, that some of the coding and decoding was undertaken by those in his pay. One of his key agents was Charles Paget from a Catholic family in Staffordshire, who entered Walsingham’s service in 1581. He came to Paris and, with his impeccable Catholic credentials, was employed by Archbishop Bethune. Detail of the scheming taking place on Mary’s behalf could now be fed to both James and Elizabeth, but Mary remained unaware that her correspondence was being closely examined.

In October 1582, Walsingham recruited another mole, Lauron Feron, a clerk in the French Embassy in London. Through him, he learned that the Catholic Francis Throckmorton was visiting the embassy at night and had travelled to Madrid and Paris to contact Mendoza, the Spanish ambassador, about an invasion plan. In late 1583, it was found that Throckmorton was acting as Mary’s courier to take letters in cipher to Mendoza, despite her continued public assurances that she was not involved in any scheming. Her correspondence was now kept under surveillance. Mendoza was still promoting a plot to place Mary on the English throne with backing from Pope Gregory XIII, Philip II, the Guises and the Jesuit leader Robert Persons. The Duke of Guise was to lead the Spanish backed force, hoping to attract English Catholic assistance on arrival. Paget attempted to limit the potential danger by trying to persuade Guise not to seek Spanish help. Further evidence of the plan arose, when, at Walsingham’s instigation, the Dutch authorities intercepted a ship travelling to Scotland, carrying the Jesuit Creighton, ‘a person deep in conspiracy’. Immediately before his arrest, he tore up and threw overboard a paper describing the detailed plan, but providentially, the pieces blew back on deck, where they were carefully reassembled.

Walsingham had Throckmorton followed, and, in November 1583, he was arrested at his London home. He had just enough warning to destroy a letter to Mary and to have a casket of fatal correspondence conveyed to the Spanish ambassador. Yet searches revealed lists of English Catholics, who might support a Spanish invasion, and sites for a foreign landing. Throckmorton confessed everything under torture. Mendoza was summoned before the Privy Council and, in January 1584, was given fifteen days to leave the country. Walsingham did not want to use his evidence to charge Mary, as this would have blown the cover of Feron, who was continuing to send him copies of all her correspondence received at the embassy. Yet the discovery of Throckmorton’s activities caused a huge public outcry against her.

Castelnau, the French ambassador, was also thoroughly implicated in the plot. Instead of publicly humiliating him, Walsingham blackmailed him as an accessory to the ‘Throckmorton plot’ and forced him to reveal his correspondence with Mary in full. Feron was no longer needed as a mole. Despite having at last identified a plot, which provided incontrovertible evidence of Mary’s treasonable activities, Elizabeth refused to act against her. Burghley advised Walsingham to strengthen the security round her and, in August 1584, persuaded Parliament to make it treasonable for a Jesuit to set foot in England. In October, Walsingham launched a Bill, which became law in February 1585 as the Act for the Surety of the Queen’s Person. This required Englishmen to pledge their allegiance to Elizabeth under oath and they were required to bring about the death of those plotting against her. Even Mary offered to sign it, calling on God to witness that she was not aware of any conspiracy against Elizabeth, nor would she give her consent to them. Yet two days later she was again issuing instructions for the launch of the Spanish invasion.

The fatal blow for Mary started in late 1585, when Walsingham again managed to infiltrate the delivery mechanism for her secret correspondence. He still hoped to implicate her in a Catholic plot, knowing that no scheme could succeed without her approval. His agents were now so well trusted among the English Catholic hierarchy that their support seemed greater than it was, bolstered by so many of his men. With Paulet controlling access to her, Walsingham was able to block her clandestine correspondence. With his double agents infiltrating Bethune’s staff in Paris, he now set a snare to catch her.

One of those plotting to assassinate Elizabeth and place Mary on the English throne was Gilbert Gifford of a well-connected Staffordshire Catholic family. He had the assistance of George Gifford, his cousin, of John Savage, a failed priest much under his influence, and of the fanatical John Ballard, an ordained soldier priest sometimes known as Fortescue. As an able linguist, Gifford was recruited onto Bethune’s staff, where he also met Paget, and was soon aware of all new conspiracies to free Mary. He now offered to provide a delivery system to enable her to receive her correspondence from Paris, which was piling up at the French embassy in London, and immediately set off for England. On arrival, in December 1585, he was immediately arrested and taken to Walsingham. It may have been Paget, who tipped Walsingham off about his plans. Walsingham now blackmailed Gifford to become another double agent, and Gifford seems to have enjoyed the thrill of it all. He came to a pact with Walsingham that he would drop any further involvement in his conspiracy, but would allow Thomas Phelippes to intercept Mary’s correspondence. Phelippes was an absolute genius at deciphering codes.

Gifford employed a brewer to hide letters in a small waterproof case pushed through the bung hole of the beer barrels being delivered from Burton to Chartley, where Mary was being held. He then presented himself at the French embassy in London offering to carry Mary’s correspondence. The ambassador handed the letters over, and Gifford took them to Walsingham, who in turn gave them to Phelippes to decipher and copy. Phelippes carried them to Staffordshire, where they were returned to Gifford, who handed them to the brewer. Unknown to Gifford, Phelippes bribed the brewer to show the correspondence to Paulet. This resulted in the brewer being paid twice, once by Paulet and once by Mary’s secretaries. He then asked a higher price for his beer! Mary’s replies followed a similar route in reverse, although this took two months. After copying them, Phelippes passed decoded versions to Paulet and Walsingham, who kept Elizabeth closely informed. The originals were then resealed by Arthur Gregory, an expert in this skilful art, and continued on their intended route to the French embassy in London.

While Walsingham now had a mechanism for reading Mary’s correspondence, he needed a plot to implicate her against Elizabeth. He encouraged his double agents in Paris to identify someone to take on Gifford’s original scheme with Gifford’s former colleagues. Bethune’s office was soon visited by an attractive twenty-five-year-old English Catholic, Sir Anthony Babington, a wealthy, intelligent and romantic squire from Dethick in Derbyshire, who relished the opportunity. In June 1586, Mary was told that Babington was approved as a contact and the French embassy advised her that he held a despatch for her. On 25 June, she asked for it to be delivered via Gifford’s beer barrel route. The letter was thus examined by Walsingham. Having laid the snare, he needed only to sit back and wait, confident of success. He was kept aware of the detailed plot, as it developed, through their correspondence, which was decoded by Phelippes. Surrounded by a clique of naïve young Catholic noblemen, Babington was out of his depth. He began to have cold feet, not least because he was interviewed by Walsingham three times before his arrest to judge whether he too could be persuaded to defect and to implicate Mary. When he wanted to back out, Walsingham had to send Gilbert Gifford to restore his resolve. He was now the titular leader of a plot to murder Elizabeth, put together by Walsingham’s agents and based on Gifford’s original scheme.

With encouragement from his fellow conspirators, Babington wrote in code to Mary with a detailed plan, unequivocally seeking consent to murder Elizabeth and to free her. Walsingham saw the letter and awaited Mary’s reply. Her main objective was to gain her freedom. If the price of her liberty was Elizabeth’s assassination, she would go along with it and wrote back in code giving her approval. Mary was now caught, and Phelippes wrote a gallows mark on the outside of his deciphered copy before forwarding it to Walsingham, and sent the original on its way to the French embassy with a forged postscript in code asking for the names of the conspirators. When Babington saw this, he realised the deception, and Walsingham had to act before he was fully prepared. He decided ‘it is better to lack the answer than to lack the man’. The conspirators faced a traitor’s death, by when Gilbert Gifford had quietly left England and was safely on the Continent from where, on 3 September, he asked Walsingham to settle a bill for £40.

Mary’s letters and ciphers were sent to London, where Walsingham scoured through them for incriminating evidence, but she had carefully destroyed the crucial correspondence with Babington, not realising that Walsingham had copies of everything. Her secretaries were dragged from her side and taken to London. After interrogation, they were shown a copy of the letter they had written on Mary’s behalf and confirmed its authenticity. Her English secretary remained imprisoned for a year, but Walsingham returned her French secretary to France. With fears of an invasion continuing, Elizabeth was horrified to learn of Mary’s involvement, unaware of the part played by Walsingham’s agents. At her insistence, Mary was isolated as far as possible from her servants, and she told Paulet to ‘let your wicked murderess know how with hearty sorrow her vile deserts compelleth these orders’. Walsingham became concerned that, by depressing her further, she might take her life before being publicly tried.

Mary’s trial at Fotheringhay was a foregone conclusion. Yet she did not let Walsingham get away which it completely. She accused him of manufacturing the plot by taking her ciphers and forging the letters himself. This was pretty close to the truth and Walsingham was forced to stand to defend his honour, averring,

God is my witness that as a private person I have done nothing unworthy of an honest man, and as a Secretary of State, nothing unbefitted of my duty.

Yet he admitted being ‘very careful for the safety of the Queen and the Realm’.

The issue now was to persuade Elizabeth to sign the death warrant. Walsingham chose this time to unearth another scheme, apparently being developed by Châteauneuf against Elizabeth, and he used this as an excuse to place him under house arrest. It is entirely possible that this was another of his fabrications, but Burghley visited Châteauneuf at the embassy and blackmailed him into agreeing to Mary’s execution. When Elizabeth eventually signed the warrant, she gave instructions for it to be taken to Walsingham, who was ill at home. She quipped: ‘I fear the grief thereof will go near to kill him outright’! She still did not want the warrant used and asked Paulet to arrange Mary’s death in accordance with the Act for the Surety of the Queen’s Person. Paulet was horrified and refused to act without proper authority. In the end Burghley had had enough and sent the warrant, which resulted in Mary’s execution. When news was brought to Elizabeth, Walsingham was diplomatically ill, and in a show of fury for the benefit of the diplomatic community, she blamed everyone.

Despite Walsingham’s success in providing the means to bring Mary down, he was never rewarded by Elizabeth. He lived on until 1590, but she never approved of his shadowy methods with his network of spies continually infiltrating plots against her Crown.