Note: This article deals only with Cecil’s involvement with Scotland and Mary Queen of Scots.

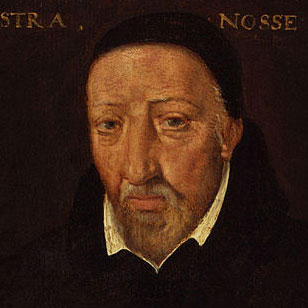

William Cecil was born on 13 September 1520 and was educated at Stamford School and St John’s College Cambridge. Although he gained a reputation as an academic, he did not sit his degree. On arriving in London, he joined the service of Edward Seymour, 1st Earl of Hertford, later Duke of Somerset, who became Protector for his nephew, Edward VI. Cecil went with him to Scotland on the third of the ‘Rough Wooings’ and was present at the Battle of Pinkie Cleuch in 1547, when the Scots were routed. In 1548, he became Master of Requests, and Somerset’s Private Secretary. Although he was placed in the Tower when Somerset fell from power in 1550, he ingratiated himself with Protector Northumberland and joined his service, becoming Chancellor of the Order of the Garter. As a staunch puritan, he used his growing influence to appoint the young John Knox as a chaplain to Edward VI. He signed (apparently reluctantly) the Instrument promoting Lady Jane Grey to the throne ahead of Mary and Elizabeth Tudor, and was lucky to survive under Mary, but he placated her by taking mass. He remained supportive of Elizabeth while she was under house arrest, and became her Secretary of State as soon as she became Queen in 1558.

Throughout Cecil’s career he was determined to avoid the experiences of the reign of ‘Bloody’ Mary Tudor and was determined to prevent another Catholic from succeeding to the English throne. When his efforts to persuade Elizabeth to marry came to nothing, he faced Mary Queen of Scots as her dynastic heir, followed by Lady Margaret Lennox and her son Henry Stuart Lord Darnley, all of whom were adamantly Catholic. Although Elizabeth wanted to retain a dynastic succession, even the nearest Protestant pretender, Lady Mary Grey had married without Elizabeth’s consent and was deemed unsatisfactory.

With Mary married to Francis II of France, Cecil faced the danger of Protestant England having French dominions on two fronts. He provided clandestine support to the Lords of the Congregation, a group of Protestant nobles, led by Lord James Stewart, to challenge Mary Queen of Scots’ mother, the Queen Regent, who was trying to protect her daughter’s Scottish throne with the assistance of French troops. Although Elizabeth was reluctant to interfere in a rebellion against an anointed Queen, she saw the logic in trying to protect England’s backside. When both the Queen Regent and Mary’s husband, Francis II, died during 1560, Mary was destined to return to Scotland to take up her throne.

Cecil would have preferred Lord James to have taken the Scottish Crown, but he was illegitimate and lacked support among his peer group. Together with William Maitland of Lethington, Cecil and Moray agreed a plan to support Mary’s return to Scotland as a Catholic Queen, provided that it was permitted to remain Presbyterian. Mary agreed to the deal, particularly because she was persuaded by Lord James that Elizabeth would then recognise her claim to the English throne.

Having returned to Scotland, Mary installed Lord James (who soon became Earl of Moray) in control of her Government and Maitland as her Secretary of State. Yet all their efforts to promote her as heir to the English throne fell on deaf ears. While Cecil wanted to dangle the prospect before her to assure her loyalty, her continued Catholicism was the real stumbling block. Despite Elizabeth wanting the correct Tudor inheritance, she refused to place Mary into a position making her the focus of future plots against her throne. While Moray and Maitland believed that if Mary married an appropriate Protestant husband, she would become acceptable, this proved not to be the case.

Mary’s choice of a husband was limited. Her initial plan was to marry Don Carlos, heir to the Spanish throne, but it became clear that he was mentally unstable, and the Spanish eventually barred him from marrying. The English wanted a Protestant, who would be loyal to England, and Elizabeth proposed her own favourite, Lord Robert Dudley, who was made Earl of Leicester to enhance his status. Cecil always mistrusted Leicester, who still hoped to marry Elizabeth. Between them, they played for time by putting forward the petulant and politically inept Darnley, never expecting Mary to take him seriously, realising that, despite their unrivalled dynastic claim, Elizabeth would see that, once married, they would be quite unsuitable.

With Darnley being tall and good looking and blessed with courtly graces, Mary fell hopelessly in love with him and they were married before his shortcomings began to be revealed. Darnley took a lead in Scottish Government to restore Catholicism and sought the Crown Matrimonial, which would have allowed him to become King in the event of the death of Mary and any children of their marriage. Mary was nervous of granting him this status until he proved himself. From now on Moray and Cecil were looking for ways to remove Mary and Darnley from the Scottish throne and to install Moray, either as King or later as Regent for the infant Prince James.

With his position as head of Government in jeopardy, Moray received funding from Cecil to start a rebellion, but, yet again, he lacked the backing of the Scottish nobles and was forced into exile in England. Maitland, who was also out of favour, found his position being usurped by David Riccio, a Catholic of doubtful ability allied to Darnley. He arranged a plan with Moray and Cecil to imply to Darnley that Riccio was enjoying an affair with Mary. He then promised him the Crown Matrimonial, if he would agree to retain Protestantism in Scotland and assassinate Riccio. Darnley agreed, but wanted the murder undertaken in Mary’s presence, so that the shock might cause her a miscarriage and probable death, leaving him as King. Maitland’s true objective was to bring Darnley down and, by association, the Queen.

When the murder took place in her presence, Mary did not suffer a miscarriage, and had the presence of mind to separate Darnley from the other conspirators. With help from the Earl of Bothwell, she escaped with Darnley to Dunbar, from where she returned to Edinburgh in triumph for the birth of her son, James. Again Cecil and Moray had been thwarted, but Mary was exasperated with Darnley and asked her nobles to find the means of gaining a divorce. It was soon found that a Catholic annulment would make James illegitimate and, without Mary’s knowledge, the nobles agreed to murder Darnley, and put Bothwell, who they disliked, in charge of the arrangements. Mary, who was unaware of the murder plan, had decided to soldier on with her marriage, which had the benefit of protecting her claim to the English throne.

Moray and Maitland now worked with Cecil to isolate Bothwell and his henchmen as the sole conspirators in the murder, although several other nobles were involved. They also wanted to bring Mary down, and decided, in advance, to sow rumours that she had been involved in an affair with him, thus portraying the murder as a crime of passion. To give this quite implausible idea credence, it was essential that Bothwell was persuaded to marry Mary. This made it important to avoid an investigation of what had happened. Although Darnley’s father, the Earl of Lennox, insisted on Bothwell being brought to trial, no evidence was presented and he was exonerated. Bothwell and Mary were then persuaded to marry, but as soon as they had agreed, the nobles took up arms against them forcing them to surrender at Carberry Hill. Bothwell was allowed to escape to stop the real story coming to light and Mary was held without trial at Lochleven, where she was forced to abdicate in favour of a Regency by Moray for the infant James, who was now King.

Cecil was intimately involved in and retained all the detailed evidence of the murder, much of which were depositions taken under torture. None of this stood up to critical examination. When Mary escaped from Lochleven and came to seek Elizabeth’s help in England, there had to be an investigation. Maitland, who had access to Mary’s correspondence, manipulated some of her letters to demonstrate her involvement with Bothwell in a log running romance in advance of the murder. Inevitably the evidence was inconsistent and sometimes contradictory, so that Cecil was at pains to avoid it being tabled. In the end he arranged the investigation so that the letters were briefly mentioned, but then withdrawn. Mary was found innocent, but sufficiently tarnished in character to be held under house arrest in England. Moray returned to Scotland as Regent.

Maitland who had married Mary Fleming, one of Mary’s ‘Four Maries’ (ladies-in-waiting), was already showing sympathy for Mary’s plight. He approached the Duke of Norfolk, the premier English peer, who had chaired the first part of Mary’s investigation to consider marrying her. Norfolk had strong Catholic sympathies and was at the opposite end of the English political spectrum to the ‘low born’ Cecil. He disapproved of an anointed queen being deposed and was in favour of marrying her, with the prospect of her becoming the English queen. Yet no one dared to tell Elizabeth. When some of Norfolk’s allies started the Northern Rising to support Mary’s accession to the English throne, the proposed marriage came to light and Elizabeth arranged Norfolk’s execution. Mary was lucky to survive, but her support in both Scotland and England was generally political, being fostered by those who wanted to bring down either Moray or Cecil. Her supporters in Scotland were sufficiently powerful to arrange for both Moray and Lennox, his successor as Regent, to be assassinated. Sir William Kirkcaldy, who had originally been an ally of Moray, managed to hold Edinburgh Castle on Mary’s behalf until 1573.

On the death of the long live Marquess of Winchester in 1572, Cecil was made Lord Treasurer, and was created Lord Burghley. Although he remained Elizabeth’s principal adviser, her ‘spirit’, the more shadowy Sir Francis Walsingham, her ‘moor’, became Secretary of State. Walsingham was determined to wipe out remaining pockets of English Catholicism and saw Mary as the catalyst for Catholic plotting. He went to great lengths to implicate her in one of the plots to oust Elizabeth and infiltrated conspiracies with double agents. He even went to the lengths of planting a plot and intercepted Mary’s correspondence. Sir Anthony Babington took charge of a plan riddled with Walsingham’s men, and arranged for Mary’s coded correspondence to be deciphered and read. Mary was caught out. Cecil organised a trial where the only possible outcome was her execution. Mary played the part of a Catholic martyr to the full, and Elizabeth reluctantly signed her Tudor cousin’s death warrant. Mary was executed at Fotheringhay Castle on 8 February 1587.

By now Burghley was aged sixty-six and he started to hand over his position next to the Queen to his second son, Robert. In 1592, he suffered a collapse perhaps from a stroke or heart attack, and progressively moved to the back stage. Yet he remained on close terms with Elizabeth who tended him in his final illness. Imperceptibly he persuaded her that the role of monarchy needed to be accountable to the people. He died in London on 4 August 1598. Without Burghley as her mentor, the final five years of her reign were blighted by her frustrating inability to take decisions. This paved the way for James VI, in 1603, to be welcomed as a breath of fresh air after her death by Robert Cecil.